Join us as we travel across time, exploring landmarks that reflect the ancient Greek and Roman eras, the grandeur of the Byzantine period, and the splendor of Ottoman design. Each site carries a story, revealing layers of historical significance that have shaped the nation’s identity.

Welcome to a journey through famous architecture in Turkey! Have you ever been curious about Turkey’s most iconic buildings and the stories they hold? In this post, we’ll delve into these wonders, exploring their profound connection to Turkey’s vibrant cultural heritage.

Prepare to immerse yourself in Turkey’s diverse architectural history as we embark on this captivating exploration together.

Table of Contents

Hagia Sophia

ARCHITECTS: Isidoros of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles

Istanbul, 532-537

Built between 532 and 537 AD by Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia is the pinnacle of classical Roman architecture. Designed by Isidoros of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles, it drew inspiration from ancient knowledge, particularly Heron of Alexandria’s work on statics. This engineering marvel combines arches and columns sourced from across the empire, symbolizing imperial power. Despite early collapses, its dome remains unmatched in harmony and beauty, surpassing even later achievements like Brunelleschi’s Florence Cathedral.

Hagia Sophia, meaning “Divine Wisdom,” retained its name after Sultan Mehmed II’s conquest in 1453. He established a foundation to preserve its legacy. The building endured challenges, including damage during the Fourth Crusade (1204–1261) and multiple structural failures. Emperor Justinian reinforced it with massive columns, but Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan’s ingenious support ensured its lasting strength.

The crowning glory of the Roman Empire, Hagia Sophia became the Ottoman Empire’s premier mosque. It underwent significant restorations, including by the Fossati brothers under Sultan Abdulmecid. A monumental book documenting its grandeur was published with Ottoman funding, though the Russian Tsar declined to contribute.

Hagia Sophia symbolizes human ingenuity and resilience, bridging centuries of history and empires.

SELIMİYE MOSQUE

ARCHITECT: Mimar Sinan

Edirne, 1568

The mosque, regarded as Mimar Sinan’s masterpiece, dominates the city’s skyline with its 31.30-meter-diameter dome and four towering minarets featuring three balconies each, positioned on the city’s highest hill. Representing the pinnacle of Sinan’s architectural innovation, this structure evolves from his earlier designs with domes supported by 4 and 6 legs, culminating in this grand dome standing on 8 legs. Its breathtaking interior features half-domes supporting the central dome, alongside an intricately crafted ornamental complex that enhances its magnificence.

DİVRİĞİ Great MOSQUE

ARCHITECT: Ahlatlı Hürrem Şah

Sivas, 1228

The grand mosque-hospital complex, completed between 1228 and 1243 in Divriği, stands out as a remarkable architectural achievement despite its seemingly modest origins. Divriği was not a significant urban center at the time, and the patrons, Mengücek Bey Ahmet Şah and Melike Turan Melek, did not hold prominent political roles. This reflects a concept still relevant in Turkish culture today: groundbreaking architectural works can arise regardless of the commissioners’ political influence or the location’s size.

A particularly rare and noteworthy detail is that the hospital was commissioned for a woman, an unusual practice in the medieval Islamic world, except in Turkish-speaking regions. This highlights an exceptional cultural tradition deserving recognition.

The mosque-hospital complex is a testament to Anatolia’s role as a creative crossroads during the medieval period. Its design integrates elements from Georgian, Armenian, Iranian, and even European Gothic architecture, making it a unique architectural masterpiece for its era. This synthesis of diverse influences exemplifies the rich cultural fusion that defined medieval Anatolia, solidifying the complex’s global significance.

SULEYMANIYE MOSQUE

ARCHITECT: Mimar Sinan

Istanbul, 1551

At the heart of the fifteen-part Süleymaniye Complex—comprising madrasahs, hospitals, baths, and tombs—stands the iconic Süleymaniye Mosque. Built in the 16th century, this architectural marvel not only ranks among the most important symbols of Istanbul but also holds a special place in the oeuvre of Mimar Sinan. As one of the finest examples of Classical Ottoman architecture, it is the crown jewel of the complex, celebrated for its location, innovative construction technology, harmonious design, and luminous interior.

Often described as a product of Sinan’s journeyman period, the Süleymaniye Mosque draws comparisons to Hagia Sophia due to its similar load-bearing system and layout. However, Sinan’s advancements in construction technology set Süleymaniye apart. Its transparent walls and uninterrupted interior create a serene, light-filled, and human-centered experience.

What makes Süleymaniye an enduring symbol of Istanbul is not only its commanding position atop one of the city’s hills but also its holistic design. The mosque appears to seamlessly emerge from its elevated location, a testament to Sinan’s masterful integration of architecture with the natural landscape. This thoughtful, harmonious design has solidified its status as one of Istanbul’s most cherished landmarks.

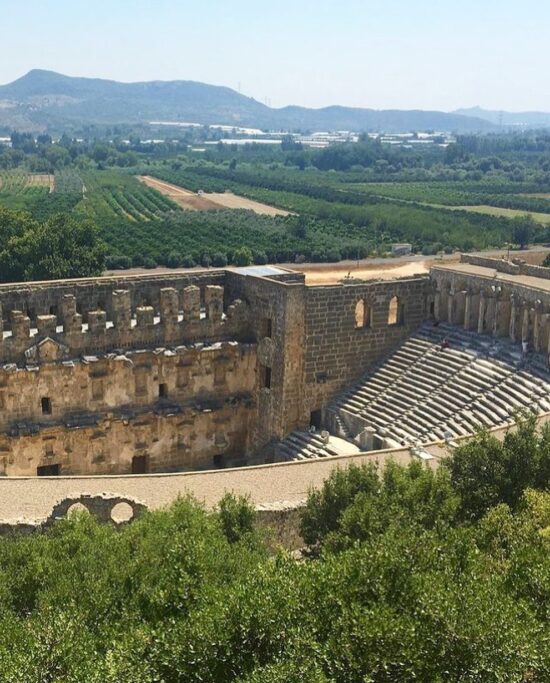

ASPENDOS

ARCHITECT: Zenon

Antalya, 138

Using the natural slope of the land it rests on, this amphitheater shows the practical design of early theaters while taking it to a higher level with advanced construction techniques. By incorporating arches and vaults, it transforms from a simple structure into an impressive and enduring architectural work, both functional and visually striking.

Its layout follows a semicircular plan, with the stage perfectly attached to the flat edge of the circle. The arched gallery above the audience area matches the stage structure in height, forming a balanced and unified whole. This seamless design adds to its beauty and provides excellent acoustics, ensuring sound travels clearly throughout the space.

This theater is a remarkable example of its time, skillfully combining practicality and innovation into a structure that continues to captivate and inspire today.

Göbeklitepe

Şanlıurfa, 9,600 BC

Göbeklitepe is a temple area 15 km from Urfa, approximately 300 meters in diameter, and 15 meters high, 20 of which have been determined, 9 of which have been excavated, and 4 of which date back 12 thousand years. This group of monumental structures, built during the period when humans were hunter-gatherers, before the transition to settled agricultural society and the discovery of iron, consists of T-shaped stones, each weighing approximately 50 tons, carved into the main rock at the base, 7 meters high, 3 meters wide at the top, with animal motifs on them, and standing stones positioned around them in a circular plan. The importance of these temples, which were later filled with soil for protection, is that they have enabled the rewriting of history by moving the history of civilization from 5 thousand years to 12 thousand years ago.

ATATURK CULTURAL CENTER

ARCHITECT: Hayati Tabanlıoğlu Istanbul, 1946

The AKM held deep significance as an iconic symbol of Istanbul’s cultural identity and a cornerstone of the city’s collective memory. While it could have been celebrated as a landmark representing Turkey’s modern architectural history, its legacy was overshadowed by its association with political polarization, reflecting broader divisions within the country.

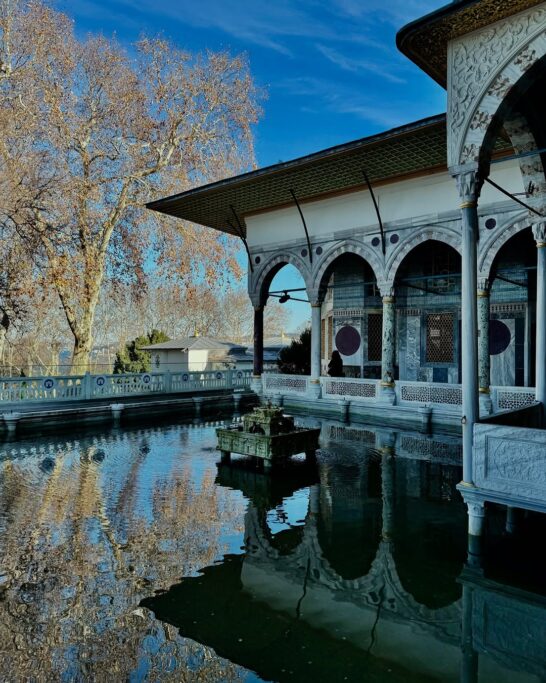

TOPKAPI PALACE

ARCHITECT: Alaüddin Davud Ağa

Istanbul, 1460

Topkapi Palace owes its enduring presence in engravings, paintings, photographs, and other visual depictions of Istanbul not only to its unique architectural features but also to the harmonious and refined relationship it established with the topography of Sarayburnu. Changing and evolving, the palace resembles a symphonic composition woven into the landscape.

For instance, the vertical prominence of the Justice Tower, the highest structure within the complex, creates a dramatic crescendo when viewed alongside the rhythmic alignment of the kitchen chimneys. The palace’s design integrates landscape elements such as walls, courtyards, and gardens, forming poetic spatial fragments. These elements not only resonate within their own configurations but also enhance the urban fabric when considered alongside earlier structures like Hagia Sophia, creating a layered and timeless visual dialogue.

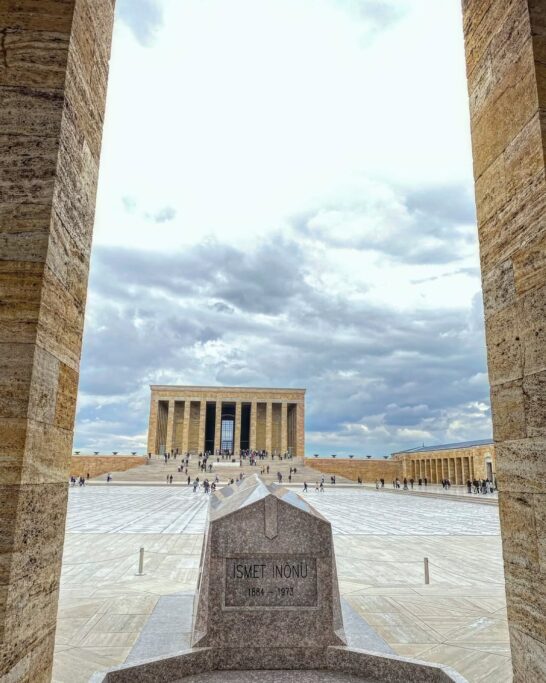

ANITKABIR

ARCHITECTS: Emin Halid Onat-Ahmet Orhan Arda

Ankara, 1944

Anıtkabir is much more than a physical structure; it is a revered place of pilgrimage. Thoughtfully situated on Rasattepe, overlooking Ankara, the entire complex is designed with careful attention to every detail of the visitor’s journey.

The experience begins with a green corridor that gently ascends toward the summit, followed by the Lion Road and the vast Square, each element serving to prepare the visitor for the Monument itself. This planned progression allows the Monument to be viewed from multiple perspectives while offering sweeping panoramas of the capital city, blending personal reflection with a sense of national identity.

Upon reaching the Monument, visitors encounter a beautifully proportioned and skillfully reimagined example of the monument-temple typology. Rooted in a tradition that dates back to antiquity, its design exudes timeless reverence and grandeur, making Anıtkabir a powerful symbol of collective memory and national pride.

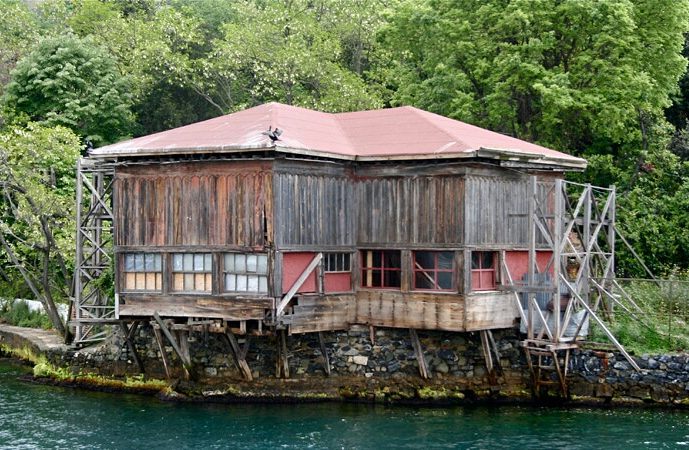

FLORYA ATATURK MARINE MANSION

ARCHITECT: Seyfi Arkan

Istanbul, 1935

Seyfi Arkan’s remarkable design stands as one of Turkey’s most significant examples of modern architecture, symbolizing the era when the new architectural language aligned with the socio-cultural modernization ideals of the Republic under Mustafa Kemal. This single-story structure, elevated on large piles, is connected to the shore by a striking 90-meter-long bridge. Constructed in just 48 days, it features wood as its primary material, complemented by specially designed fittings and elements.

The L-shaped plan of the building reflects a thoughtful functional separation between the living and service areas, tailored to meet the unique care requirements of Mustafa Kemal during the final years of his life. Its placement beside Florya public beach not only highlighted the modern leisure activity of sea swimming, which had gained popularity during the period, but also symbolized Mustafa Kemal’s connection to the public.

Over time, the building underwent significant renovations, with certain parts replaced by reinforced concrete. Today, this historically and architecturally important structure serves as a museum, preserving its legacy and its role in the narrative of Turkey’s modernization.

SUMELA MONASTERY

Trabzon, 365

The Sumela Monastery, perched at an astonishing height of approximately 1400 meters above sea level and carved into the side of a mountain, is a marvel that never fails to amaze with each visit. Believed to have been constructed before Hagia Sophia, its origins in the 4th century AD make it an extraordinary achievement, especially when considering the technical knowledge of the time. Its dramatic appearance, almost like a scene from a movie, combined with its resilience through the centuries, highlights its architectural and engineering brilliance.

The monastery holds countless secrets and mysteries that continue to captivate historians and visitors alike. The unsolved mathematical equations behind its design, the daunting climb via a 100-step staircase, the six distinct terrace floors, and the enigmatic frescoes are all elements that spark curiosity. The intricate arches that channel water to the monastery, the spaces carved directly into the mountain, the steps, and the terraces showcase an extraordinary level of ingenuity for its era.

AMCAZADE MANSION

Istanbul, 1699

This divanhane, celebrated as the oldest surviving example of civil wooden architecture, is a remarkable testament to the creativity and ingenuity of its time. Its daring structural cantilevering over the Bosphorus, the uniquely low window proportions, and the striking visual effect of the wide blinds on its facade make it a true architectural fantasy.

A hallmark of Ottoman architecture, the contrast between the richly adorned interior and the understated simplicity of the exterior embodies a refined balance between opulence and restraint. Despite being currently obscured by ongoing construction, the sight of this captivating structure from Rumelihisarı each morning offers a sense of hope and joy, with the dream that its restoration will one day bring it back to its full splendor.

İstanbul Manifaturacılar Çarşısı (IMC)

ARCHITECTS: Doğan Tekeli, Sami Sisa and Metin Hepgüler

Istanbul, 1967

The IMÇ project stands as one of Istanbul’s most significant architectural achievements, offering a lasting and effective solution to a pressing urban challenge on the Historical Peninsula. When Unkapanı Boulevard was opened in the 1950s as part of the Prost plan to connect the city’s two sides, the design of the boulevard’s intersection with the Süleymaniye neighborhood, including its historic social complex, became a defining architectural and urban design issue for Istanbul.

IMÇ addressed this problem with a masterful integration of open and closed spaces, reflecting the Anglo-Saxon “met-urbanism” approach of the time, which emphasized textural city design and ground-level stratification. The cascading layout, punctuated with courtyards, creates a dynamic urban edge along the boulevard from Saraçhane to Unkapanı, seamlessly blending architectural form with its urban context.

This project successfully bridged the macro-scale urban planning considerations with finer architectural and urban design solutions, offering valuable lessons for addressing similar challenges in modern cities. Its thoughtful design and enduring functionality make it a benchmark in Istanbul’s architectural and urban planning history.

Turkish Historical Society

ARCHITECTS: Turgut Cansever and Ertuğ Yener

Ankara, 1962

This library and conference center draws heavily from local architectural traditions, shaping its design in meaningful ways. The three-story central atrium, lit from above, mirrors the organizational principles of Ottoman madrasas. It serves as a sheltered urban space, with all major activities arranged around it. The controlled use of light enhances the atrium’s public atmosphere while creating a more private feel in the surrounding areas.

Modern building materials are placed alongside traditional ones, blending innovation with heritage. The poured-in-place concrete frame contrasts with the rugged texture of Ankara stone and the polished elegance of Marmara marble. Aluminium window frames coexist with wooden screens, achieving a seamless harmony between old and new. The jury highlighted how this building stands apart from the International Style that has shaped Ankara’s architecture since the 1930s. It demonstrates how tradition can inspire modern designs and guide a shift toward a more fitting architectural language.

BASILICA CISTERN

Istanbul, 527

The Basilica Cistern, one of Istanbul’s most fascinating ancient landmarks, was built during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in the sixth century. Situated just a short walk from the iconic Hagia Sophia, it is the largest surviving Byzantine cistern in the city, featuring an impressive 336 marble columns that once supported its function as an underground water reservoir.

The rectangular structure, more than 100 meters long, can be accessed via a 52-step staircase. Its 336 columns, each standing nine meters tall, are arranged in 12 rows of 28. The columns showcase a mix of Corinthian and Ionic styles, with a few featuring the simpler Dorian design. The cistern’s walls, standing 4.8 meters high, enclose an area of 9,800 square meters.

Originally designed to filter and store water for the Great Palace and its royal surroundings, the Basilica Cistern once included gardens surrounded by colonnades facing Hagia Sophia. However, after the Byzantines relocated from the Great Palace, the cistern fell into obscurity. Rediscovered during the Ottoman era, it was used as a dumping ground for waste and even corpses.

In the 1980s, the Basilica Cistern underwent significant renovations and was finally opened to the public, allowing visitors to experience its breathtaking architectural and historical significance.

GRAND BAZAAR

Istanbul, 1460

The Grand Bazaar, established in 1461, is a mesmerizing labyrinth that captivates first-time visitors with its intricate design and sheer scale. Resembling a maze, it invites exploration and intrigue, serving as both a commercial hub and a major tourism destination in Istanbul.

Architecturally, the Bazaar’s Bedesten consists of 15 distinct sections, standing as a monumental example of Turkish design. The decorative Bedesten, in particular, is a hallmark of Turkish architecture, blending utility and aesthetics in a way that exemplifies the inner character of the Grand Bazaar.

Historically, the Bazaar was renowned for its thick iron-reinforced bases, where traders safely stored their valuable documents and jewelry. Over time, original stones and bricks have been replaced with brickwork and rubble, yet the essence of its architectural brilliance remains. The Grand Bazaar continues to stand as a masterpiece of Turkish architecture, combining history, culture, and craftsmanship in a timeless design.

Rüstem Paşa Mosque

ARCHITECT: Mimar Sinan

Istanbul, 1578

The Rüstem Paşa Mosque, designed by the renowned architect Mimar Sinan in 1561, is a historic structure situated above the bustling Weavers’ Market (Hasırcılar Çarşısı) in the Eminönü district of Istanbul’s Tahtakale neighborhood. Commissioned by Grand Vizier Rüstem Paşa, son-in-law of Süleyman the Magnificent, the mosque stands as one of Sinan’s significant works, following the Rüstem Paşa Madrasa and the Rüstem Paşa Mosque in Tekirdağ. Historical records indicate that construction likely concluded in 1563.

Located near the Golden Horn, the mosque occupies a strategic low-lying area beneath the Süleymaniye Mosque, integrated into a vibrant commercial hub. Built on a vaulted substructure, the mosque elevates above its dense surroundings, housing warehouses that complement the neighborhood’s mercantile nature. Adjacent to the mosque are a cemetery to the west and a square behind the qibla wall.

The mosque is a two-story structure, with the ground floor serving as a vaulted warehouse and the second floor as the mosque itself. The main facade, oriented northwest, features nine broad pointed arches leading to the warehouse. Two staircase towers flank the facade, providing access to the upper story, which includes an open-air porch overlooking the street.

The mosque’s interior and parts of its exterior are adorned with Iznik tile panels featuring intricate floral motifs. Red and white stones highlight the arches supporting the dome, while floral frescoes embellish the domes’ centers. Thuluth inscriptions and Arabic medallions add further elegance, emphasizing the mosque’s Ottoman artistry.

HAYDARPASA TRAIN STATION

ARCHITECTS: Otto Ritter and Helmut Cuno

Istanbul, 1906

Built between 1906 and 1908 during Sultan Abdulhamit II’s reign, Haydarpaşa Train Station in Kadıköy is a hallmark of early 20th-century German architecture. Designed by German architects and constructed by 1,500 Italian stonemasons, the station was named after Haydar Pasha, a key figure in the area’s history.

The station’s U-shaped design features spacious, high-ceilinged rooms and an inner courtyard. Resting on 1,100 wooden piles driven with steam rams, it highlights advanced engineering for its era. Built by the Anadolu Baghdad Company, it also facilitated goods transport with breakwaters and silos.

Haydarpaşa remains a symbol of Istanbul’s history, blending architectural beauty with practical purpose.

Dolmabahçe Palace

ARCHITECT: Garabet Balyan and Nigoğos Balyan

Istanbul, 1843

The Baroque and Rococo embellishments on Dolmabahçe Palace’s exterior highlight the strong European influence on the Ottoman Empire, while its interiors retain a distinctly Turkish character. The palace is divided into two main sections: the Mabeyn-i-Humayun on the south, housing male quarters and administrative offices, and the Harem-i-Humayun on the north, reserved for the royal women. At its center lies the grand Ceremony Hall (Muaide Salon).

The palace’s opulence is showcased in its French baccarat glass, Bohemian crystal staircase railings, gold accents, Hereke carpets of silk, cotton, and wool, vaulted glass ceilings, Marmara marble, and the iconic crystal chandelier from England.

Dolmabahçe Palace symbolizes the Westernization of the Ottoman Empire, blending Ottoman and Western architecture into a stunning fusion that reflects its role as a bridge between the East and West.

The Grand Post Office

ARCHITECT: Vedat Tek

Istanbul, 1905

The Grand Post Office, located in Istanbul’s Sirkeci district, is Turkey’s largest post office and a significant symbol of Ottoman modernization. Designed by architect Vedat Tek, the building was constructed between 1905 and 1909 during the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II. Situated near the Spice Bazaar and New Mosque, it reflects the First National Architecture Movement with its impressive stone façade, intricate decorations inspired by 16th-century Ottoman designs, and structural innovation, including iron beams for durability.

Covering 3,200 square meters, the five-story building features a grand entrance leading to a spacious central hall illuminated by stained glass. The two towers on its façade, topped with domes and metal pavilions, emphasize its grandeur. Initially serving as a hub for communication and trade, it later became the Grand Post Office in the 1930s and today houses a museum dedicated to Turkey’s postal and telecommunications history.

Artifacts in the museum include historical postal equipment, telegraph devices, and Ottoman-era stamps, showcasing the evolution of communication in Turkey. The building stands as a blend of Ottoman and Western influences, preserving its cultural and architectural significance as part of Istanbul’s historical heritage.